I’ve seen in my own healing journey, and as a guide to many others, how wrestling with a memory creates a longing for a transcript or a video of the moment.

Did my mother’s voice really sound that harsh or was I an overly sensitive child? Was I forgotten at the store for hours or did it just feel that long? Was my older sister actually jealous when my grades were praised or did I imagine that?

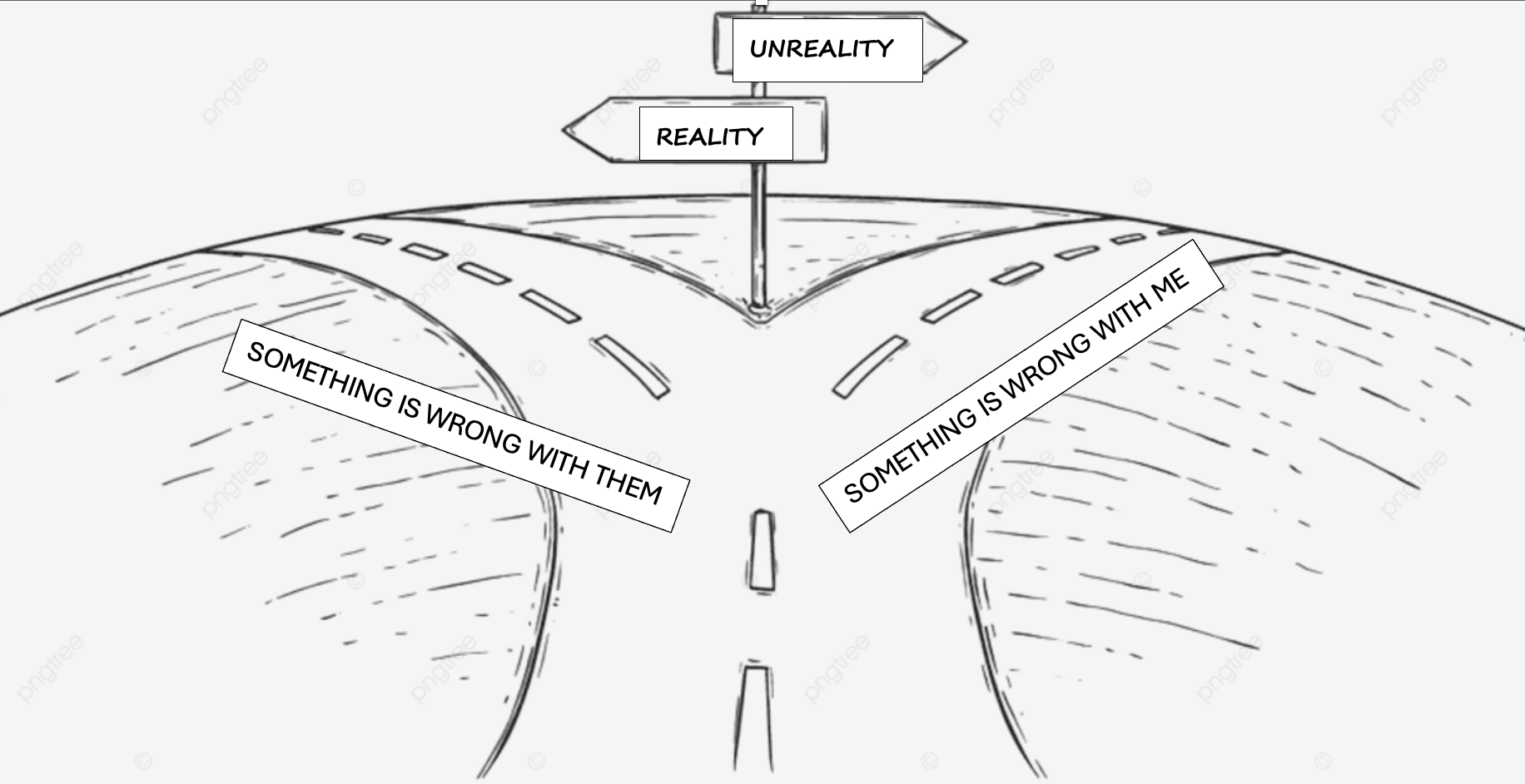

Somehow, we’ve come to believe that an accurate telling of events only comes from an outside perspective rather than learning to trust the inner experience of our mind, heart and body.

The black community in America has understood this truth since 1991.

Speaking last week on behalf of the doubts of the black community that a recording of the death of Ahmaud Arbery will result in a conviction of his murderers, Jimmy McGee, director of The Impact Movement, shared his memory (see time stamp 40:02) of when the “first video” was shared with the world:

I can tell you the first time there was a video camera that recorded Rodney King getting beat down by a whole bunch of cops. I can tell you across the nation, even though I wasn’t in LA, we all said with a big sigh, ‘Now everybody can see how we’re abused.’

The understanding was that now that it’s on video, these cops are going to be found guilty and now we can live as black people. And the riots came when they were all exonerated by a jury,

Now I know that they can see something recorded and still not be provoked to see value in my black body.

Validation of an experience doesn’t come because you have a video of the event.

Yesterday, I watched Sterling K. Brown’s video after his 2.23 mile run for Ahmaud. It is another type of “evidence”—a heart-felt description of his racial experience as a black man in American in the metaphor of being unable to breath while wearing a quarantine mask while exercising.

White America will not believe the stories of our black brothers’ and sisters’ racial experiences until we validate the inner experience of our own life stories. We need to listen to their wisdom from 19 years of disappointment—a video is impotent evidence in believing the truth of our experience.

What story have you wanted “video evidence” for in order to feel validated to speak or write about? What story do you need to tell in order to be present with the emotions of people in your life?