In his book, Love is the Way, Bishop Michael Curry tells the story of a 1993 fire that incerated the roof of his St. James parish in West Baltimore.

He writes:

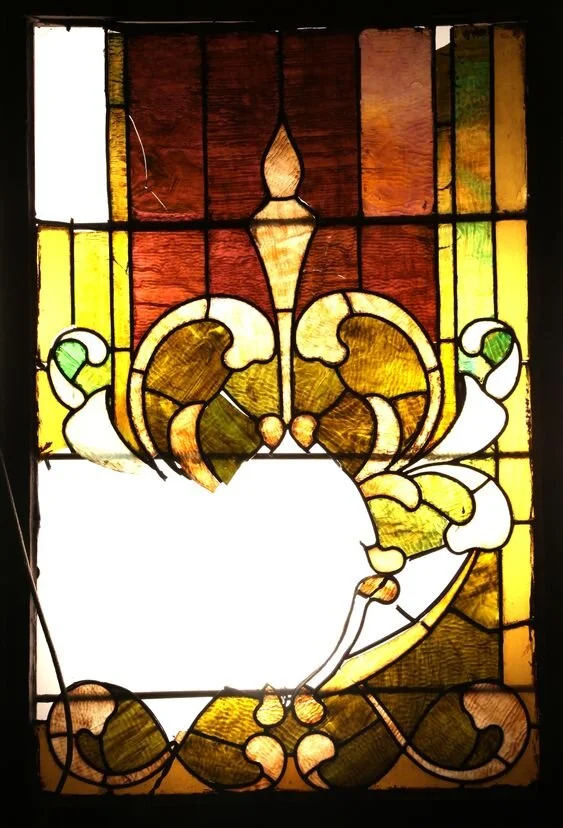

The roof was blazing when the fire chief walked up to me. ‘We’ve got a decision to make. If you don’t create another source of oxygen, the gas inside is going to build up, and it could blow out all the windows, maybe even the entire building.’ He pointed to the largest and most beautiful of all the windows, a rose stained-glass window that decorate the front of the church. ‘I need to break that window to let in the air. Do I have your permission?’ They did and it was the beginning of the end of the fire. The roof was gone, but destroying that window saved the building.

Though a decision like Curry’s is never one I want to be faced with, this vivid picture is a balm for the ways I wrestle with my own intentions. It invites me to look at the things I’ve dismantled or broken in hopes of saving something greater, and strengthens me against accusations (from within and without) that I’ve ruined things rather than fought to save them.

Whether you seen a shattering act as cruelty or kindness depends on how wide your camera angle is—are you looking at merely the beauty of the stained glass window or at an entire building being ravaged by fire?

What are you fighting to save?

What are you willing to lose in order to win?

What needs to be broken to preserve something greater?

What permission do you need to give others?

Who sees your actions as kind instead of cruel? Do you?