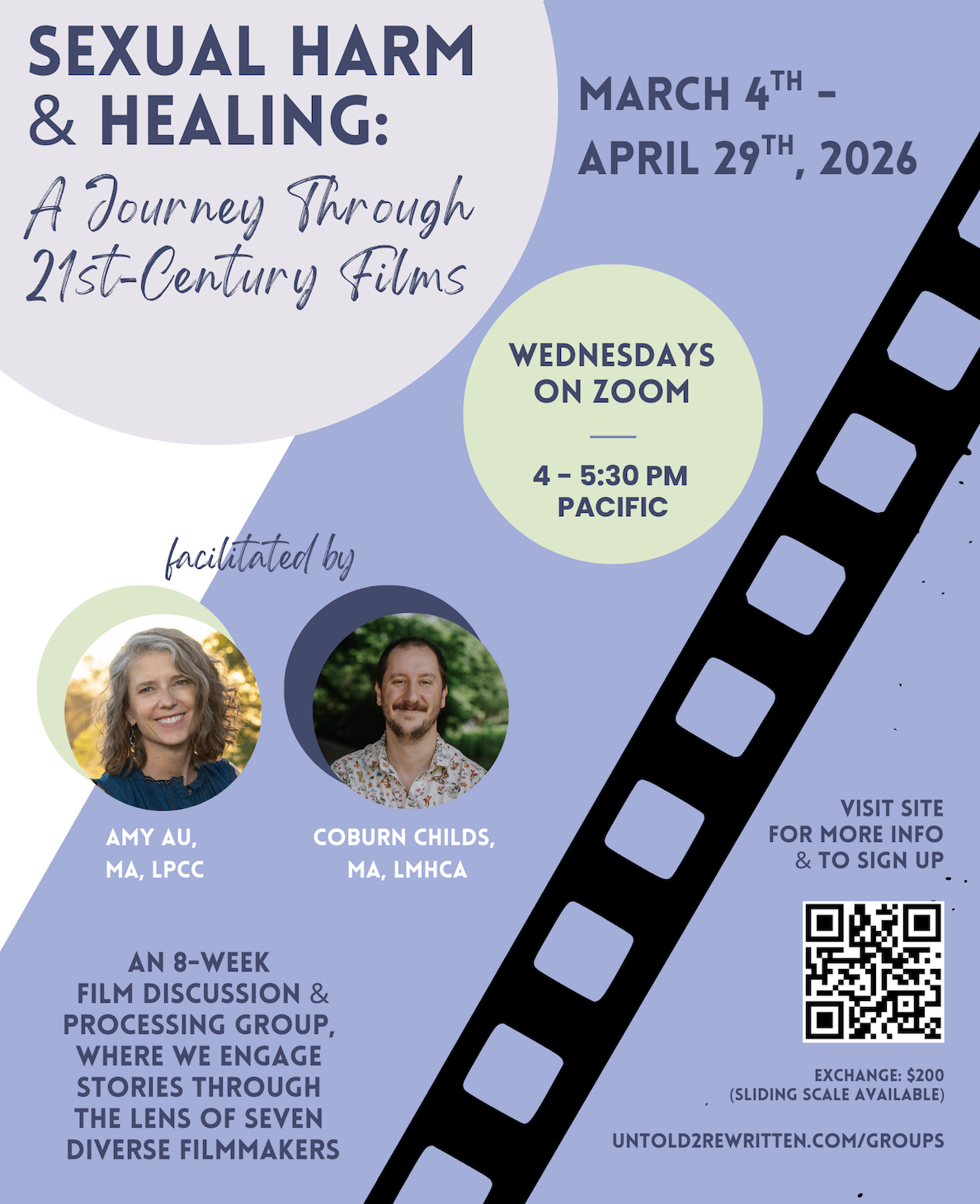

I’m so excited to share that a dear colleague, Coburn Childs, and I are offering this unique group experience beginning in March. Click on the link below to learn more details about how we’ll interact and the films we’ll discuss. Space is limited to 8-10 participants and is open to a wide range of people—those who are survivors wanting to take their next step in healing, souls who are unsure if they have experienced sexual harm, those supporting survivors and clinicians who want to expand their understanding of the complexity of this unique landscape of harm. Please reach out if you have specific questions and want to chat about whether this could be a great next step in your process!

Six Lane Highways

One of the hardest shifts to make in our healing journey is to allow intense words like trauma, abuse and neglect to have a wider meaning than we are comfortable with. It’s understandable that we prefer harm to mean one clear, obvious thing rather than a seemingly infinite sliding scale of possibilities. Much like when we hear that a mass public shooting was caused by one, mentally disturbed individual, a singular source of harm is a more soothing story. We find solace when the odds feel minimal that something tragic will find us next.

But what mental health professionals know is that narrow definitions of reality leave us stumbling around in dangerous territory without the ability to locate ourselves and validate the danger we feel. It’s like wandering in a minefield with a map of a 30 square yard area of land and being told there are only a few potential hazards to avoid, when the reality is that the dangerous zone is actually three-square acres, and the number of buried triggers is unknown. We would all traverse the ground very differently depending on which narrative we were believing.

The hard truth is that trauma, abuse and neglect are six, not single, lane highways. There is the fast lane on the far left where the reckless drivers and nice European cars speed at a neck breaking pace. Then there are the lanes in the middle where most people drive right above the speed limit, passing others more deliberately with a focus on getting to their destination on time. Then there is the second from right lane where the people who aren’t in a rush drive the speed limit, likely exiting in a few miles and not wanting to miss their turn. And then in the far-right lane are the people slowing down to get off the highway or in old vehicles or with elderly drivers not comfortable with the speed limit. Harm, trauma and abuse all have multiple speeds, not just one and knowing this means we can validate more of the pain that we feel and seek the help in healing we truly need.

Before I continue, I want to be clear that my hope in this article is NOT to encourage us to be more hypervigilance. Hypervigilance is defined as a state of excessive alertness, where our nervous systems remain constantly on guard, scanning our environments for perceived threats or dangers, even in safe situations. It’s an exhausting survival mechanism that feels like being “on edge.” While a normal protective response to danger, it becomes problematic when it persists, causing significant distress and interfering with life.

As a trauma survivor, my growth path the past several years has included being less future oriented out of fear. Instead of being consumed by the possibilities of what people will do or how things will play out, I’ve worked hard to stay more regulated in my present and confident that I will be cared for (by myself, by my resources, by those who love me) in whatever occurs that is both impossible to predict or prepare for.

Honestly, the better I have become at being less hypervigilant the more fragile and lost I have felt at times. I thought, at first, turning away from hypervigilance would mean a more peaceful, confident existence. There is some freedom that comes from less anxiety, but as I have let my ability to “feel into the future” develop the rust of underuse, I have felt more vulnerable, not less.

My hope in asserting that words like trauma are wider and deeper than we want to believe is to encourage us to listen to ourselves rather than dismiss or turn away from the truth we intuitively know in our bodies. Our path towards greater rest and freedom is not to deny the evil and harm in the world but to affirm our detecting it and let that lead and shape how we live.

Let’s start with one big word that we often underestimate in its prevalence: trauma.

The definition of trauma includes three essential aspects. A great way to remember them are the 3 Es: event, experience and effect. Trauma is not only what happens to us but also what our experience is of that event and then the effect our experience has on us. There are, of course, some events that are widely considered traumatic because they would be dysregulating for almost every human on the planet. A tsunami would be an excellent example.

A person sunbathing on a beach who detects the eerily receding of waves and then sprints inland to safety will experience the event differently than a person in a helicopter hundreds of feet above the ocean’s surface. And the effect from the experience of those different vantage points will be different for each of them. A person who makes it safely to a shelter and survives, but then later will walk through a landscape floating with dead bodies will see a different effect than someone witnessing from above the first big seismic wave hitting the shore and killing hundreds of unaware people before flying off to land miles away from the carnage. These two tsunami stories would be an example of what trauma can and does look like in the fast lane.

Middle lane experiences of trauma that I have seen from a therapist chair include divorce in families, children of parents who went through long periods of depression or chronic illness, partners taking care of a spouse with dementia for decades, and food insecurity for families living below the poverty line. These are not “easier” things to deal with than a tsunami but they are more normally occurring events so we don’t quickly label them as traumatic because they are less physically intense or more prolonged.

And finally, the slow lane may include events like an introverted preteen moving to a foreign country for a parent’s job change and entering adolescence without a vital sense of belonging. Or a company promoting a young executive over an employee in their 50s because they can pay them less for a management role because they have less seniority. Or a highly driven young athlete losing a competition because of an erroneous call by an official. All these things we would say just happen every day and we know a hundred other examples in our lifetime of these types of stories so we easily dismiss the experience it is for a particular individual and the lasting effect it can leave on their lives.

In the coming months, we will look more specifically at the different forms of abuse and neglect we can encounter in our stories. We’ll look at what the defining elements are for these experiences and try to unmask the forms of abuse and neglect in the middle and slow lanes that can go unnamed, unaddressed and unhealed in our lives for years.

Reflective Exercise:

On a piece of paper (ideally in a journal or notebook) draw a picture of a six-lane highway. Begin a list of events you experienced in your story that carried different levels of intensity and write each in one of the six lanes. I encourage you to not spend too much time thinking about where to put it, but instead let a sense of how big it felt to you at the time it happened lead you to place it in a lane. Keep in mind the 3 Es of trauma—not only the event but also the experience it was for you and the effect it had on you. Can you give each event in a lane one word to describe the experience (overwhelming, confusing, shameful, heavy, disorienting, sad, etc.) and a phrase to describe the effect it had on you (insecure, afraid of strangers, out of place with my peers, started restricting food, expecting rejection from then on, etc.)?

Headline Harm vs. Candy-Coated Harm

Nestled into a corner of the lounge on the ground floor of my TCU dormitory, I settled in to fill out an application for an international summer project with Campus Crusade for Christ. My first serious boyfriend had dumped me a few months before and I was still putting myself back together. I had cast aside what I considered a calling to teach as a missionary to fit into the vision of an advertising major who wanted to conquer corporate America, and now I was doing penitence. I wasn’t raised Catholic, but I might as well have been considering how much guilt I was carrying.

There were several short answer questions on the application, but the truly daunting part was the checklist of life experiences and moral standards. By the end of the one pager, I had checked yes in several sections: sexual abuse, divorced parents, presence of half/step siblings, parents’ remarriage, cult activity and adoption. Technically, I hadn’t been in a cult, but at the time the evangelical church considered the Masonic Lodge “on the fringe” and I had been initiated when I turned 18 as a rite of passage in my family. I also didn’t experience what is traditionally considered an adoption, but since my mom had been divorced and remarried twice and I had been legally adopted by each of her new husbands, I figured it counted. I wasn’t taking any chances. I was putting everything down.

All of this should have been concerning but the real kicker was that I had been sexually active with my boyfriend and had to explain (confess) all of that too. Not surprisingly, I wasn’t allowed to go to the Middle East that summer, which for reasons I can’t remember was my first choice, but instead my campus director pulled a favor card with his best friend, the director at LSU, and I was accept onto the team going to Hungary. Three months later I was on my first international flight, despite all the labels on my application.

Fast forward a year and I’m standing in front of a girlfriend hearing her say, “That makes so much sense with your dating patterns.” I can’t for the life of me remember her name, but I can still vividly see her tall, lean frame, white-blonde, shoulder length hair and the wheels turning in her head like she had just solved a complicated riddle. I was asking to borrow her car to drive the 50 minutes to my mandatory counseling appointment that Crusade required if I wanted to go back overseas with their one-year program after graduation. She had probably asked me about the book my counselor had assigned me—The Wounded Heart—and I disclosed that I had been molested by my stepfather from the time I was four years old until I was eight. She had seen me serial date for over a year, breaking the hearts of good guys and tolerating crumbs of attention from immature boys. She finally had the missing piece of data and now I made sense to her. I’m sure she didn’t say the word “broken” out loud but that’s how I felt. I was judged by one of the labels of what I had experienced as a young girl and finally exposed as the damaged and lost young woman I felt like day in and day out.

Now, I don’t look back and call either of these memories necessarily healthy or helpful in my healing journey, but they do speak to the usefulness of labels to signal significant harm. Now as a therapist, I call them “headline words”—the kind of events referred to in newspapers, the nightly news, and the stuff of research studies and Gallup polls that end up in required textbooks for courses like Social Work 101. These headline words in my story initially felt like curses in my 20s but now in my 50s, I’ve become incredibly grateful for them.

Let me be clear, I am NOT grateful for the things that I endured in my story as a child. It has taken years to separate the abuse in my story from the way it shaped me and the gifts I possess from how I survived. Now, because of decades of emotional work, I have come to see how useful it’s been to have clear words to describe dark chapters of my life. I have words that are clearly understood as affecting my development, my relationships, and my emotional health. I have words for events that everyone knows leave a mark and take a long time to heal. I have never, ever, had anyone ask me, “Why are you in counseling?” or for that matter, “Why are you still in counseling?” I would have never thought to be grateful for the headline words in my life story that the world at large agrees are egregious wrongs if it weren’t for watching my peers who grew up in “perfect” homes struggle to make sense of their own damage.

If there’s one thing I don’t envy of anyone it’s growing up in a “good Christian family.” My home was a million miles from healthy, but it was a clearly toxic concoction that should have been a legitimate CPS report, not a whitewashed tomb.

Anyone who has ever heard about my childhood has said a kind and empathetic version of “I’m so sorry that all happened to you.” You hear that enough and it helps you stay sane on days when your disorganized attachment style brings you to tears. But what about those who were wounded, even abused or neglected, by people in their family but never had a bruise to show for it? What about those who suffered through a sugar-coated toxicity that never sounded as bad out loud as it felt for their nervous systems as young children? And what about when there’s no physical action that crosses a clear, legal line or a phrase someone says that raises eyebrows or makes a police report?

Some of the most powerful therapeutic moments I’ve stumbled into are ones when a person, who seems to come from the antithesis of my upbringing, hears me say something to the effect of…

“The presence of clear, recognizable harm in my story has made it easier to pursue healing. I have so much respect for those who must excavate harm with tiny instruments like the ones archeologists use. One wrong move and it feels like you destroy all the evidence of the past.”

Whether your story is primarily “headline harm” or “candy-coated harm,” I hope the content we’ll explore in the coming months will validate what you’ve lived through, help you feel more seen by yourself and others, and leave you feeling saner and companioned on your healing journey.

Next week we’ll dive into what are the different ways harm can show up in our lives, but until then I encourage you ponder the experiences in your story you have labels for and the ones you don’t.

Reflective Exercise:

Start a list of both the headline harm and the candy-coated harm that comes to mind when you look back at your home growing up. Write down as much as you can think of, whether it feels big enough to make a list or not. Take time to wrestle with what isn’t easily named. Feel free to add phrases from books or movies, imagery or analogies, and body sensations on your candy-coated list. You might need to draw, cut out magazine pictures, get poetic or use a lot of hyphens when trying to put down on paper what feels impossible to catch on camera.

New Year's Gift: Substack Content Free for January!

I’m so excited to kick off this year of publishing healing resources, childhood trauma recovery research, and giving survivors a doorway into community with one another. For January, all four weeks of content will be fully available for free to give everyone an opportunity to decide if they want to subscribe for $10 a month going forward. Click here to preview January’s overview and subscribe to get Monday’s first January article and discussion question. Thanks for reading and please share with anyone you know on a journey to deeper healing!

“Forsaking, aching breaking years,

the time and tested heartbreak years.

These should not be forgotten years.

The blinded years, the binded years,

the desperate and divided years.

These should not be forgotten years.

Remember.”