I am not yet confident enough to explain what it means to be anti-racist, but I’m starting to understand what it is not.

I lived outside the US for 17 years.

That’s not enough.

I didn’t vote for Trump.

That’s not enough.

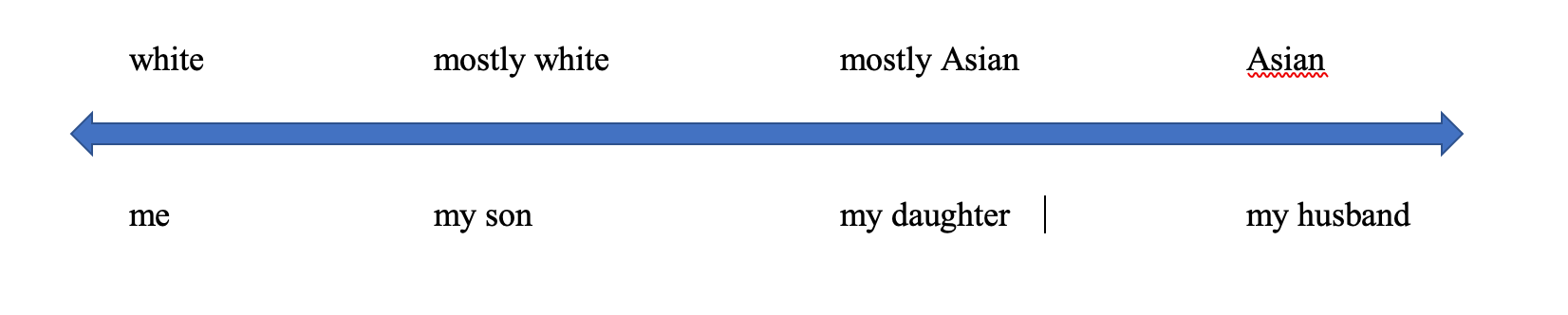

I married a person of color.

That’s not enough.

I’m raising biracial children.

That’s not enough.

I even read Austin Channing Brown’s book I’m Still Here before it was on the New York Time’s Best Seller list.

Even that’s not enough.

I have a feeling that being anti-racist isn’t what I do outwardly but more about what I do when white supremacy manifests itself through me.

A few months ago I was in a room with beautiful people (talking about diversity and equity no less) and a colleague handed me a piece of paper that he later took back because of a printing error.

“Indian giver,” I called him jokingly.

My Native American colleague sitting besides me instantly gasped and confusion, terror and panic flooded me. It took only a few minutes in a short conversation with her to understand the magnitude of what I had said, but it took days for the shame to dissipate.

I left that encounter horrified that it had never occurred to me that the term was derogatory. I was tempted to believe that had been an unfortunate exception in how I communicate around people of color, but I know it wasn’t. I grew up in a small town outside Austin and I’ve said that phrase hundreds of times. It was just the first time I’d had gracious help interpreting it.

I am not exempt from being racist.

And I’d like to think that was a one time event, a singular blemish on my heart to love all people but this weekend reminded me it wasn’t.

Saturday, I was with a community of church volunteers helping a black client move into her new apartment. At one point she told us we could leave the mattresses in her living room and her kids would help her move them later. Before I could blink, the sentence, “You have plenty of slave labor if you need it,” began rolling off my lips. I caught myself mid sentence. Again, horror, terror and panic came. I don’t know if anyone heard me in the crowded, chattering room but I heard myself.

And I’m still wrestling with the shame.

I’m a social worker for God’s sake. I married a person of color. I raise biracial children. I’m hardly even American. I know better.

None of that is enough. None of that makes me exempt.

White supremacy is in me. It’s in my language, my frames of reference, my lens. It’s the reason I get a large tax return as a homeowner. It’s everywhere. It’s in my DNA.

How do I purge my very DNA?

I’m still answering this question but I know part of the process will include asking the pastor of the church and the mom we were all helping if they heard the first half of my sentence. It’ll involve repair.

But I’m not ready to do that yet. I’m waiting a few days for my shame to dissipate and my courage to build. It’ll take a few days before I approach them so that I’m ready to care for them instead of inviting them to care for me.

I am not exempt from being racist. I wonder if any of us are.